David J. Phillip/AP Photo

Hurricanes, large and small, have eluded U.S. shores for record lengths of time. As population and wealth along parts of the U.S. coast have exploded since the last stormy period, experts dread the potential damage and harm once the drought ends.

Three historically unprecedented droughts in landfalling U.S. hurricanes are presently active.

A major hurricane hasn’t hit the U.S. Gulf or East Coast in more than a decade. A major hurricane is one containing maximum sustained winds of at least 111 mph and classified as Category 3 or higher on the 1-5 Saffir-Simpson wind scale. (Hurricane Sandy had transitioned to a post tropical storm when it struck New Jersey in 2012, and was no longer classified as a hurricane at landfall, though it had winds equivalent to a Category 1 storm.) The streak has reached 3,937 days, longer than any previous drought by nearly two years.

(Brian McNoldy)

Twenty-seven major hurricanes have occurred in the Atlantic Ocean basin since the last one, Wilma, struck Florida in 2005. The odds of this are 1 in 2,300, according to Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher from Colorado State University.

Florida hasn’t seen a hurricane of any intensity since 2005’s Wilma, which is shocking considering it averages about seven hurricane landfalls per decade. The current drought in the Sunshine State, nearing 11 years, is almost twice as long as the previous longest drought of six years (from 1979-1985).

(Brian McNoldy)

Sixty-seven hurricanes have tracked through the Atlantic since Florida’s last hurricane impact. The odds of this are about 1 in 550, Klotzbach said.

Even the entire Gulf of Mexico, and its sprawling coast from Florida to Texas, have been hurricane-free for almost three full years, the longest period since record-keeping began 165 years ago (in 1851). The last hurricane to traverse the Gulf waters was Ingrid, which made landfall in Mexico as a tropical storm, in September 2013.

Scientists have no solid explanation for the lack of hurricane landfalls. The number of storms forming in the Atlantic over the past decade or so has been close to normal, but many have remained over the ocean or hit other countries rather than the United States.

A study published by the American Geophysical Union in 2015 said the lack of major hurricane landfalls boiled down to dumb luck rather than a particular weather pattern. “I don’t believe there is a major regime shift that’s protecting the U.S.,” said study lead author Timothy Hall from NASA.

A “recurring” area of low pressure near the U.S. East Coast in recent years may have repelled some storms, argue Klotzbach and Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami. But McNoldy still says “luck is really 99 percent of it [the drought].”

Adam Sobel, a climate scientist at Columbia University, cautions that the drought in no way invalidates global warming predictions or the expectation that storms will grow more intense in future decades. The “notion that the hurricane drought in the Atlantic has somehow disproved the consensus projections of climate science is wrong, because the drought is still a relatively short-term fluctuation in a single basin, while the projections are for long-term global trends,” he writes on his blog.

And as impressively long as the various droughts are, McNoldy said there have been numerous storms that have almost ended each of them in recent years.

So the drought is hanging on by a thread. A single major hurricane striking Florida’s Gulf Coast, McNoldy said, would break all three standing droughts simultaneously.

Concerns about preparedness and increasing coastal population

It’s only a matter of time before the luck reverses and storms start bombarding the U.S. coast again.

Growing coastal populations and lack of recent hurricane activity, from Florida to Texas, raise concerns about the nation’s readiness.

“Hurricanes are going to hit the U.S. again and people are going to be shocked by the magnitude of the disaster,” said Roger Pielke Jr., professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

The Associated Press reports Florida’s coastal communities have added 1.5 million people and almost a half-million new homes since 2005, the last time there was an onslaught of storms.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projects that by 2020, the U.S. coastal population will have reached 134 million people, 11 million more than in 2010.

“Hurricane damage and destruction is a direct function of how much accumulated wealth there is,” Pielke said. “We’ve put a lot of stuff along the coast. If we’re in this 10-year drought, loss potentials in some places may now be two times higher than it was a decade ago.”

Experts are conflicted as to whether residents — after a long break from dealing with hurricanes — will be well-prepared when the next storm threatens.

Kim Klockow, a visiting scientist with NOAA who studies meteorology and social behavior, said one major concern “is that communities might not be as practiced in getting prepared simply because they haven’t had to do it in a while.”

But she said she doesn’t think residents will tune the storm threat out. “I’m not sure if the long period of calm will make them less concerned,” Klockow added.

Gina Eosco, a social scientist who works with National Weather Service through the consulting firm Eastern Research Group, agrees with Klockow. “Coastal residents are savvy,” she said. “They understand that by living on the coast they are taking some risk. An individual does not necessarily need direct experience to decide to evacuate or prepare for a hurricane.”

Still, Pielke said consequences are inevitable for out-of-practice communities. “You can do all the talking and planning you want, but until you go through a hurricane, you don’t know what you’re up against,” he said. “The lessons of inexperience are pretty costly.”

Eosco offered this advice: “I cannot overstate the importance of preparing before a storm happens. This starts with a conversation. Each resident with experience should share it with their new neighbors.”

Ref.: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2016/08/04/the-u-s-coast-is-in-an-unprecedented-hurricane-drought-why-this-is-terrifying/?utm_term=.1acf26a5ccce

……………..

Why We Won’t Be Ready for the Next Hurricane Harvey Either

The devastating flooding in Houston left by Hurricane Harvey has drawn the normal questions about the government response, from whether officials should have issued an evacuation order to why they chose to release reservoir water.

But flooding experts say the biggest government failure likely came in the years that preceded the storm as the city allowed developers to build new communities with little regard for flooding projections and the federal government promised to subsidize flooding losses.

And, while Hurricane Harvey’s damage in Houston will make the city the storm the most damaging in years, the city is far from the only place in the U.S. vulnerable to disastrous flooding as a result of bad policy. Every state has experienced a flooding event in recent years costing the federal, state and local governments billions of dollars. And experts say sea level rise and increased precipitation related to climate change could exacerbate the problem in the coming years.

“People have for years and years wanted to live along the water,” says Laura Lightbody, who directs the flooding program at the Pew Charitable Trusts. And “there are some perverse incentives in place from a policy perspective to continue to build and live along those areas, which is making them more at risk.”

In Houston, flooding experts attribute the flooding in large part to a lack of zoning laws that have encouraged explosive property development with little regard to the environmental impact and strain on infrastructure. A 2016 ProPublica report warned that as Houston became the metropolis of 2 million people it is today, developers paved over empty land that would have otherwise absorbed rainwater. In situations with extreme storms, rainwater congested waterways vulnerable to overflowing.

Most parts of the country have enacted zoning ordinances, unlike Houston, but local rules often fail to account for the latest science on flood risk. And developers in communities without any such local measures still need to comply with federal standards set by the Federal Emergency Management Agency if they build in flood hazard regions, which would be inundated by a flood that has a 1% chance of occurring in a given year. Those standards require builders to elevate new or substantially renovated structures above that threshold, among other rules.

But preparing for a 100-year flood still leaves communities vulnerable. By the nature of probability, 100-year floods will happen occasionally and leave substantial damage when they do, and some states already require developers to build to more stringent standards. With the climate changing as a result of human influence, it can be difficult to anticipate what will constitute a 100-year flood a few decades down the road.

“We expect everywhere that flooding rains will increase,” said Ken Kunkel, an official at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, following deadly 2015 flooding in South Carolina. “You can build it now for today’s climate, but you may not be quite in tune to what the climate will be in 50 years.”

In cases where 100-year floods, or worse, do occur, the federal government assumes much of the risk leaving many homeowners with little incentive to move away from a vulnerable property. Many repeatedly flooded properties have received the value of their property—or greater—in payouts from the federally administered National Flood Insurance Program, leaving the program more than $24 billion in debt.

The Obama Administration took steps to address the flooding issue in 2015 with an executive order that required developers who receive federal rebuilding dollars after a natural disaster to do a better job accounting for climate science. Under the order, developers were required to build to the 500-year flood elevation, build three feet above the 100-year flood elevation or to use the best-available climate science to come up with a better standard.

President Trump reversed that measure—which he described as too heavy a burden for developers—in a speech at Trump Tower earlier this month as a part of a broader infrastructure push. “No longer will we tolerate one job-killing delay after another,” he said. “No longer will we accept a broken system that benefits consultants and lobbyists at the expense of hardworking Americans.”

But research has shown that spending more up saves money in the long run. Every dollar invested in mitigating the risk of natural disaster saves $4 in relief and rebuilding costs, according to a Pew report. In Houston, that would have meant billions.

Ref.: http://time.com/4919224/hurricane-harvey-houston-policy/

………………….

I’ll end this with an article from the “green” rent grant seeking criminals camp of FAKE (Man Made) Climate Change.

Do you ever wonder why they just call it “Climate Change” these days? Where does the “Man Made”-part go? Because that is what they mean. Using that logic: Almost 12 years without a hurricane 3 or bigger making landfall in the US .. all of a sudden, literally within 48 hours, there you have it: Man Made Climate Change!

.. and some of them even call themself scientists! ???

Story from Politico

Harvey Is What Climate Change Looks Like

In all of U.S. history, there’s never been a storm like Hurricane Harvey. That fact is increasingly clear, even though the rains are still falling and the water levels in Houston are still rising.

But there’s an uncomfortable point that, so far, everyone is skating around: We knew this would happen, decades ago. We knew this would happen, and we didn’t care. Now is the time to say it as loudly as possible: Harvey is what climate change looks like. More specifically, Harvey is what climate change looks like in a world that has decided, over and over, that it doesn’t want to take climate change seriously.

Houston has been sprawling out into the swamp for decades, largely unplanned and unzoned. Now, all that pavement has transformed the bayous into surging torrents and shunted Harvey’s floodwaters toward homes and businesses. Individually, each of these subdivisions or strip malls might have seemed like a good idea at the time, but in aggregate, they’ve converted the metro area into a flood factory. Houston, as it was before Harvey, will never be the same again.

Harvey is the third 500-year flood to hit the Houston area in the past three years, but Harvey is in a class by itself. By the time the storm leaves the region on Wednesday, an estimated 40 to 60 inches of rain will have fallen on parts of Houston. So much rain has fallen already that the National Weather Service had to add additional colors to its maps to account for the extreme totals.

Harvey is infusing new meaning into meteorologists’ favorite superlatives: There are simply no words to describe what has happened in the past few days. In just the first three days since landfall, Harvey has already doubled Houston’s previous record for the wettest month in city history, set during the previous benchmark flood, Tropical Storm Allison in June 2001. For most of the Houston area, in a stable climate, a rainstorm like Harvey is not expected to happen more than once in a millennium.

In fact, Harvey is likely already the worst rainstorm in U.S. history. An initial analysis by John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas state climatologist, compared Harvey’s rainfall intensity to the worst storms in the most downpour-prone region of the United States, the Gulf Coast. Harvey ranks at the top of the list, with a total rainwater output equivalent to 3.6 times the flow of the Mississippi River. (And this is likely an underestimate, because there are still two days of rains left.) That much water—20 trillion gallons over five days—is about one-sixth the volume of Lake Erie. According to a preliminary and informal estimate by disaster economist Kevin Simmons of Austin College, Harvey’s economic toll “will likely exceed Katrina”—the most expensive disaster in U.S. history. Harvey is now the benchmark disaster of record in the United States.

As with Katrina, Harvey gives us an opportunity for an inflection point as a society. The people of Houston didn’t choose this to happen to them, but what happens next is critically important for all of us.

Climate change is making rainstorms everywhere worse, but particularly on the Gulf Coast. Since the 1950s, Houston has seen a 167 percent increase in the frequency of the most intense downpours. Climate scientist Kevin Trenberth thinks that as much as 30 percent of the rainfall from Harvey is attributable to human-caused global warming. That means Harvey is a storm decades in the making.

While Harvey’s rains are unique in U.S. history, heavy rainstorms are increasing in frequency and intensity worldwide. One recent study showed that by mid-century, up to 450 million people worldwide will be exposed to a doubling of flood frequency. This isn’t just a Houston problem. This is happening all over.

A warmer atmosphere enhances evaporation rates and increases the carrying capacity of rainstorms. Harvey drew its energy from a warmer-than-usual Gulf of Mexico, which will only grow warmer in the decades to come. At its peak, on Saturday night, Harvey produced rainfall rates exceeding six inches per hour in Houston, and its multiday rainfall total is close to the theoretical maximum expected for anywhere in the United States.

Weather patterns are also getting “stuck” more often, boosting the chances that a storm like Harvey would stall out. Some scientists have linked this to melting Arctic sea ice, which reduces the strength of the polar jet stream and weakens atmospheric steering currents that can otherwise dip down and kick a storm like Harvey on its way. To be sure, a storm like Harvey might have been possible in the absence of climate change, but there are many factors at play that almost assuredly made it more likely.

Adapting to a future in which a millennium-scale flood can wipe out a major city is much harder than preventing that flood in the first place. By and large, the built world we have right now wasn’t constructed with climate change in mind. By continuing to pretend that we can engineer our way out of the worsening flooding problem with bigger dams, more levees and higher-powered pumping equipment, we’re fooling ourselves into a more dangerous future.

It’s possible to imagine something else: a hopeful future that diverges from climate dystopia and embraces the scenario in which our culture inevitably shifts toward building cities that work with the storms that are coming, instead of Sisyphean efforts to hold them back. That will require abandoning buildings and concepts we currently hold dear, but we’ll be rewarded with a safer, richer, more enduring world in the end. There were many people in Houston already working on making that world a realityeven before Harvey came.

If we don’t talk about the climate context of Harvey, we won’t be able to prevent future disasters and get to work on that better future. Those of us who know this need to say it loudly. As long as our leaders, in words, and the rest of us, in actions, are OK with incremental solutions to a civilization-defining, global-scale problem, we will continue to stumble toward future catastrophes. Climate change requires us to rethink old systems that we’ve assumed will last forever. Putting off radical change—what futurist Alex Steffen calls “predatory delay”—just adds inevitable risk to the system. It’s up to the rest of us to identify this behavior and make it morally repugnant.

Insisting on a world that doesn’t knowingly condemn entire cities to a watery, terrifying future isn’t “politicizing” a tragedy—it’s our moral duty. The weather has always been political. If random whims of atmospheric turbulence devastate one neighborhood and spare another, it’s our job as a civilized society to equalize that burden. The choices of how to do that, by definition, are political ones.

Climate change hits the vulnerable in a community hardest. It is no different in Houston with Hurricane Harvey, where even if an evacuation would have been ordered, countless thousands of people wouldn’t have had the means or ability to act. There is simply no way to safely evacuate a metro area the size of Houston—6.5 million people spread across an area roughly the size of Massachusetts.

The symbolism of the worst flooding disaster in U.S. history hitting the sprawled-out capital city of America’s oil industry is likely not lost on many. Institutionalized climate denial in our political system and climate denial by inaction by the rest of us have real consequences. They look like Houston.

Once Harvey’s floodwaters recede, the process will begin to imagine a New Houston, and that city will inevitably endure future mega-rainstorms as the world warms. The rebuilding process provides an opportunity to chart a new path. The choice isn’t between left and right, or denier and believer. The choice is between success and failure.

Ref.: http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/08/28/climate-change-hurricane-harvey-215547

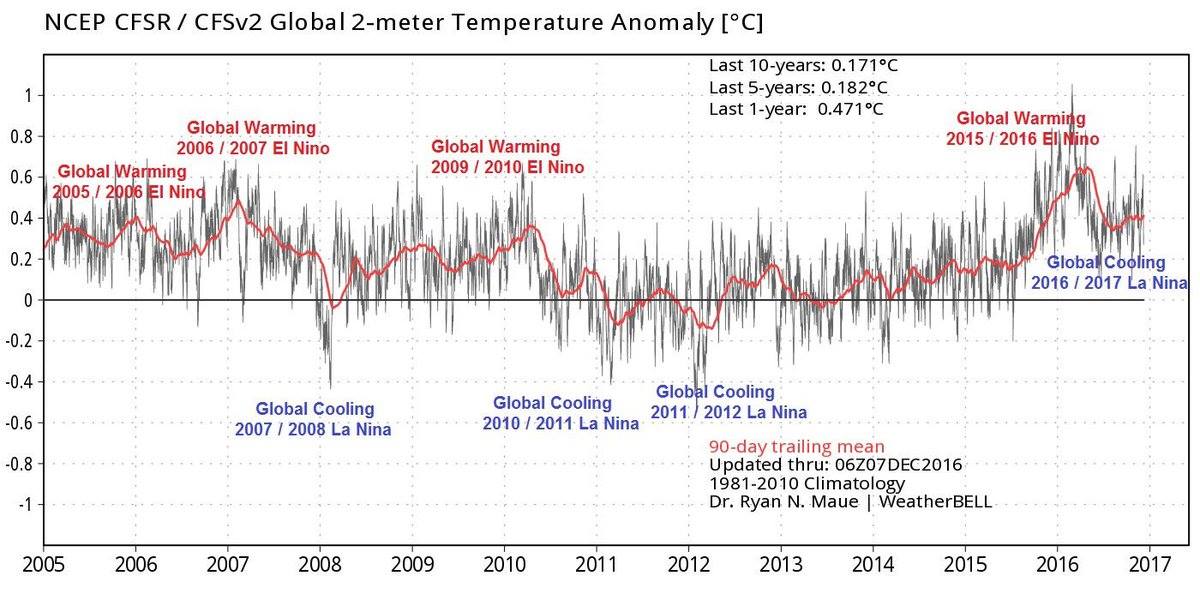

But look at the actual data:

Yeah, i know, no climate change, neither man made or natural, that has to be a problem, right!?

No, not at all, they just tweak a little here, adjust a little there and finally, 140% homogenization on top of that. What? Examples? Ok, here’s one:

.. and another:

Now, who would need to change anything if the data really showed there was a problem? That would be like cheating on a test despite of knowing all the answers.

R. J. L.