Image: It’s only getting worse: ‘Our Planet’ film crew is still lying about walrus cliff deaths: here’s how we know

By Paul Homewood

Environmentalist Jim Steele wrote this historical account of Pacific walrus conservation, that has a lot of relevance to recent events:

The walrus is another example of improving environmental stewardship. Valued for its oil and ivory tusks, the Pacific walrus was subjected to intense commercial slaughter in the mid 1800s, and by the early 1900s, many worried they would soon go the way of the dinosaurs. Although population estimates have always been highly uncertain, as hunting was progressively limited, Pacific Walrus populations “increased from 50,000 to 100,000 animals in the late 1950s to more than 250,000 animals by 1985,” and they are believed to have now reached their maximum carrying capacity.557 As walrus numbers rebounded, they have crowded together at historic coastal haul-outs (Haul-outs are land locations where walruses congregate when not swimming). However some advocates are using the walrus’ recovery as evidence of ecological disruption caused by global warming and the loss of sea ice. But their fears would vanish if they had a more historical perspective.

In 1923 Captain Joseph Bernard published an account in the Journal of Mammalogy about the inspiring conservation efforts he had observed in the village of Ingshong on the Siberian coast.558There the wisdom of walrus conservation, dressed in the trappings of shamanic beliefs, had fostered a dramatic comeback in local walrus abundance.

When Capt. Bernard had first visited the village of Ingshong, he met an ordinary hunter named Tenastze. Eighteen years later, Tenastze had become Chief. His rise to the top began when he gathered together the men of Ingshong and neighboring villages to discuss a decade of failed walrus hunts and disappearing herds. Walruses had once come to rest on their beaches in countless numbers, but the beaches were now empty. Tenastze believed that there was no one in the village looking after the spirit of the walrus and summoned a small group of shamans to peer more deeply into the problem.

After days of extended drumming and an induced trance, the shamans reported that indeed someone had offended the spirit of the walrus and poisoned the land. To break the spell of evil, the people had to choose a strong chief who promised to guard the walrus’ spirit.

Their first step was to sacrifice the first walrus that presented itself to the village’s hunters. After ritualistic preparation, its skull was placed on a long stick. Holding the other end of that stick, the strongest man in the village would attempt to lift the skull in response to each question. Like a shaman’s version of the Ouija board, questions were directed to the walrus spirit. If the strongman was unable to lift the skull, it was a negative answer. If the spirits wanted to respond positively, the spirits imbued the man with enough strength to lift the skull. One by one, the names of all the men vying to be the new chief were offered to the walrus spirit. Only when the name Tenastze was spoken could the strongman lift the skull. (Although I love the story’s ending, the skeptic in me can’t help but wonder if Tenastze paid off the strongman.)

Now in charge, Tenastze quickly designated a round-the-clock guard to insure that the walruses were not disturbed. When the walruses first appeared in the coastal waters, fires were not allowed and alcoholic drink was forbidden. Shortly thereafter, a lone venturous walrus finally settled on their beach, and spent the night undisturbed. After each feeding foray, that walrus returned again and again and each time brought more and more walruses. By the time the autumn sun was retreating south, and the winter freeze beginning, several hundred walruses had come ashore. Only then were the people allowed to take their allotted kill; most walrus were permitted to go away unharmed. The walruses seemed unaffected by this limited hunt, and the next year many more came ashore. As the years passed, the herd grew to such proportions that villagers told Bernard, “last year the beach was so crowded when the walruses hauled there, many walruses were crushed to death just from overcrowding.”558

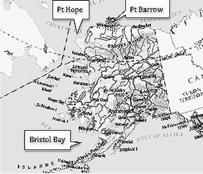

In 1925 Bernard again wrote in the Journal of Mammalogy, advocating for walrus sanctuaries in Alaska to the south of Barrow.559 He contrasted the more conservation-minded village of Ingshong to the settlement of Point Hope on the Alaskan Coast. Thirty years before, the walruses had hauled out by the thousands and some would even wander into town. However the traders, whalers, and Inuit of the settlement were all too quick to shoot any weary walrus coming ashore. Subsequently, for the last twenty years live walruses had become a rare sight on that beach.

The European settlers of that time had embarked on a withering onslaught, motivated by a lucrative ivory market. In just a few decades the only surviving walruses were the ones that had learned to avoid coastal haul-outs, finding greater safety on the ice floes or more remote islands. Nomadic Inuit hunters showed no greater restraint than the Europeans. They followed the wary walrus herds out onto the ice floes. Although walrus meat was highly valued, ivory tusks brought much greater returns. Along the 200 miles of shoreline near Pt Barrow, Alaska, Bernard counted 1000 walrus corpses washed ashore. One third of the corpses still retained their tusks; although shot, they had managed to slip into the waters before the hunters could cleave their tusks. The nightmare was likely far greater than evidenced by mere shoreline counts. If Bernard counted 1000 rotting carcasses washed ashore by the westerly winds, how many more were carried by the currents out to the Arctic Ocean, or to other distant beaches?

From 1900-1930, the annual harvest of Pacific walrus averaged 5000 per year. Despite growing concerns voiced by Bernard and others, that figured doubled to 10,000 per year between 1930 and 1950. The Pacific walrus was seemingly headed for extinction. Fearing this may be the last chance to observe living walruses, Francis Fay began compiling one of the most complete accounts of the ecology and biology of the Pacific Walrus for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. After more than two decades of research, “The Ecology and Biology of the Pacific Walrus” was published in 1982.560

The 1950s were the 20th century’s nadir of walrus abundance. Over-hunting of whales and walruses had been so severe, the native Yupik of the St Lawrence Island found themselves on the verge of starvation. The Yupik had dodged an earlier threat of extirpation in 1879 when disease was introduced by visiting whalers. When John Muir and a Smithsonian naturalist visited the island they were horrified to find huts strewn with hundreds of dead bodies. There were few survivors. Although the Yupik population had only rebounded to just one-third of their pre-epidemic population, the slaughter of whales and walruses now denied the surviving Yupik adequate sustenance. According to Fay, “If remedial food supplies had not been provided by Federal and State governments, the islanders probably would have been afflicted again by starvation and death in 1954-55.”

When the walrus were plentiful in the 1800s, they had hauled out in great numbers on beaches. Fay reported that of “numerous coastal hauling grounds that were used on the Siberian coast in the early part of the century, only three remained in use by the mid-1950’s.” There were just too few Tenastze to guard the walruses. Thanks to hunting restrictions, the walrus rebounded. As populations returned to historical peak abundance, they began returning to former coastal haul-outs. Most recently walruses returned to an Alaskan beach about 140 miles southwest of Barrow. It was the general location that Captain Bernard wanted protected as a walrus preserve, and news of the walruses’ return would have certainly caused the good captain to celebrate. But not the global warming advocates. A stampede, most likely provoked by a hunting polar bear, left several trampled walruses. Although historically tramplings had been associated with great abundance, advocates spun it as proof of deadly CO2.

The Huffington Post published the following: “ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Trampling likely killed 131 mostly young walruses forced onto the northwest coast of Alaska by a loss of sea ice, according to a preliminary report released Thursday.” “Obviously it’s a real tragedy, and it’s one we’re going to see repeated more and more as the climate warms and the sea ice melts,” said Rebecca Noblin, staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD). The CBD had petitioned to list walrus as threatened or endangered because of increased CO2 levels. The article makes the bold claim, “Were it not for the dramatic decline in the sea ice, the young walruses at Icy Cape most likely would be alive on the ice and not dead on a beach,” said WWF [World Wildlife Fund] biologist Geoff York.”

However, by all historical accounts, land haul-outs were very common in a time of abundant sea ice. The lawyers and advocates were ignoring (or ignorant of) Bernard’s 1925 lament that “Thirty or forty years ago in various places along the Alaskan coast walruses were known to haul-out in countless numbers (emphasis added).” 559 It’s also doubtful they had ever read Fay’s mid-century accounts in which death by trampling was listed as one of the “top 3 natural causes of death to walrus calves exceeded only by deaths caused by killer whales and polar bears (emphasis added).” 560

Fay’s research had compiled numerous reports depicting far greater mortality from trampling. Those deadly events happened when animals either hauled out in panic when pursued by killer whales, or when stampeded by attacking polar bears or humans. For example, in 1975, researchers reported a large number of dead animals during a stampede from a traditional hauling ground at Cape Blossom on Wrangell Island. The low-flying aircraft of the researchers had caused that stampede.560

In the heavy ice year of 1979, Fay examined the remnants of the greatest trampling tragedy yet recorded. On Punuk and St Lawrence Island, “At least 537 animals died at one haul-out area,” and approximately 400 other carcasses washed ashore from other locations. Nearly all of the dead were extremely lean, having less than half as much subcutaneous fat as healthy animals examined in previous years.” St Lawrence Island and the Punuk islands lie directly in the migratory path of the walrus’ southward journey from their summer feeding grounds in the Chukchi Sea to their wintering areas in the Bering Sea. The tramplings were spread out over both traditional haul-out locations on the Punuk Islands and in “four other locations on St. Lawrence Island where locals claimed they had not been seen in recent memory.” A more thorough investigation unearthed abundant old carcasses and bones and laboratory dating techniques revealed those “new” haul-outs had been very active in the early 1900’s before hunting pressures decimated their populations.

http://landscapesandcycles.net/hijacking-successful-walrus-conservation.html

Via https://notalotofpeopleknowthat.wordpress.com/2019/04/16/successful-walrus-conservation/