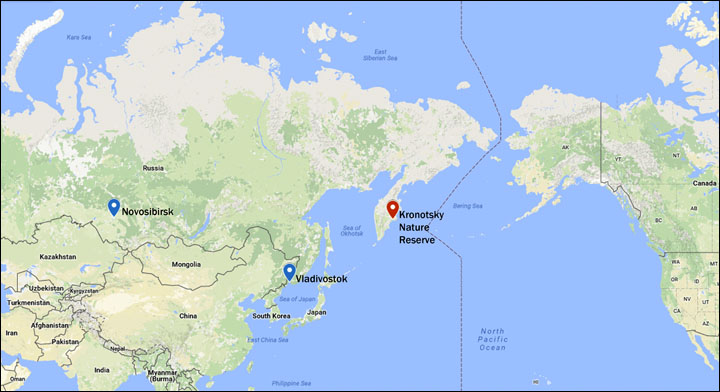

‘Some places on this planet are so wondrous, and so frangible, that maybe we just shouldn’t go there.’ Picture: Kronotsky Nature Reserve

Geysers, active volcanoes, thermal lakes, mountains, Pleistocene glaciers, cascading rivers… and a lot of bears!

Josef Stalin may not rank high on the list of great ecologists, but in 1934 he decreed that Kronotsky Nature Reserve, also now known as Kronotsky Biosphere Zapovednik, should be free of tourists and hunters, and instead be visited solely by scientists engaged in serious science.

The tyrant’s move has preserved one of the planet’s most mesmerising yet fragile treasures, and still today, while a mere few thousand travellers do now annually enter its boundaries under careful supervision, the vast majority come by helicopter on day trips, rarely exceeding five hours on the ground, or rather mostly on wooden decking so they don’t tamper with the soil, ensuring minimum interference with its ecosystem and protecting its breathtaking wildlife.

More than 80 years later, there are no hotels, no fast food cafes, and, in fact, not a single road is built into Kronotsky, on the east of the Kamchatka Peninsula, touching the Pacific, as far away from Moscow as Massachusetts.

The reserve takes its name from the perfectly-coned and snow-crowned Kronotsky Volcano. Pictures: Kronotsky Nature Reserve, The Siberian Times

Imagine if the US authorities all but banned access to Yellowstone or Grand Canyon national parks and you get a sense of the scale of the restrictions. These two parks in the US boast around 7.7 million visitors a year, whereas Kronotsky counts its trippers in the low thousands.

Probably such curbs could not have been put in place without the authoritarianism of Soviet rule; and still today, the downside is certainly that the overwhelming majority of Russians can never hope to feel a natural utopia that is, many would say, their country’s richest natural jewel.

And even those few venturing to this eastern Eden, an area larger than Cyprus or Jamaica, barely touch its rich diversity.

Yet as National Geographic writer David Quammen suggested seven years ago: ‘Some places on this planet are so wondrous, and so frangible, that maybe we just shouldn’t go there.

‘Maybe we should leave them alone and appreciate them from afar. Send a delegated observer who will absorb much, walk lightly, and report back as Neil Armstrong did from the moon – and let the rest of us stay home.’

Kronotsky is home to more than 800 brown bears, the largest protected population in Eurasia. Pictures: Igor Shpilenok

The term zapovednik has been described as connoting this: ‘a restricted zone, set aside for the study and protection of flora and fauna and geology; tourism limited or forbidden; thanks for your interest, but go away.’

It is ‘a protected area which is kept forever wild’, a ‘nature sanctuary’ and there are more than 100 in Russia of which this is the doyen.

Free largely of the tourist footprint, and free, too, of hunters, who before Stalin’s edict shot sable here (indeed it was set up as a sable hunting ground by the tsars), the natural fauna survive, and thrive, without the threat of man and his guns.

Kronotsky, for example, is home to more than 800 brown bears, the largest protected population in Eurasia, undisturbed as they fish for salmon in the tumbling waters of the reserve’s streams.

Among other animals, many endangered or threatened, others endemic to this unique reserved some 1,800 kilometres north of Japan, are the world’s largest population of the Steller’s Sea-Eagle and Aleutian sea-swallow; roaming free here are Kamchatka long horned snow sheep, safe from hunters and poachers. There are otters, the Kuril seal, sea lions and nine species of cetaceous mammals that are on the endangered species list of the Red Book of Russia.

It is a mountain river canyon where over 20 large geysers act on seven square kilometre area. Picture: @lusika33, Evgeny Vlasov, Kronotsky Nature Reserve

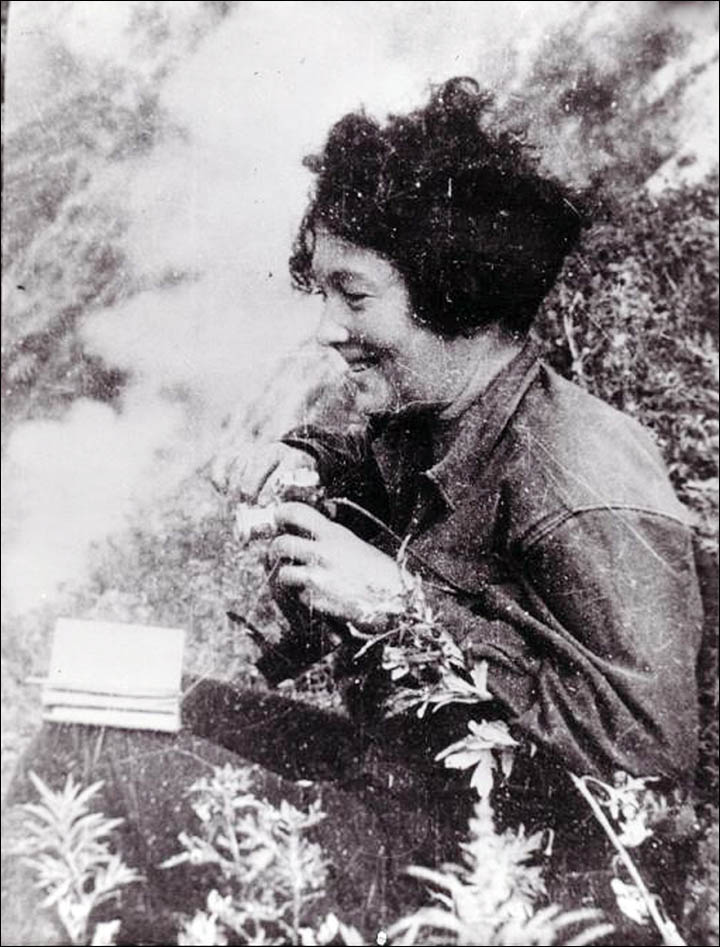

The reserve is famous for its Valley of the Geysers but, surprisingly, this remarkable site was not even known about at the time Stalin established the nature reserve here in 1934; they were only discovered seven years later by one of the scientists permitted to roam its tantalising landscapes, geologist Tatiana Ustinova.

She wanted to understand why water downstream was warmer in one river than another.

Ustinova first noticed these steaming water fountains while exploring the Shumnaya River by dog sleigh, returning several months later – around the tempestuous moment the USSR faced invasion from Nazi Germany in the West of the country – and mapped some 40 geysers.

She called the first one she discovered ‘pervenets’, meaning ‘firstborn’ yet its fate is illustrative: in 2007, a high ridge collapsed in this volcanically active landscape, and this geyser was quieted after the massive fall of rock, clay, sand and mud.

This inevitable instability is another reason to beware when calls some to open this paradise to Russian and foreign tourists.

Despite this natural sculpting of Kronotsky, the remaining geysers here, the largest complex in Eurasia, compare in significance to those better known tourist sites in New Zealand, Iceland and Chile as well as at Yellowstone.

For the scientists who have such unique access to this suddenly changing topography, it is a dream come true. As one said: ‘We are quite lucky to witness such an event… our lives are very short, and yet we witnessed it.’

Vladimir Mossolov, deputy director for science in the reserve, described the geyser valley in this way: It is a mountain river canyon where over 20 large geysers act on seven square kilometre area.

Valley of the Geysers was discovered by one of the scientists permitted to roam its tantalising landscapes, geologist Tatiana Ustinova. Picture: Kronotsky Nature Reserve

‘Each of these geysers is exceptional and unique. Each of them has its own name and character. Velican erupts thirty tons of water per one minute up to the height of a nine-storey, Troinoi (Triple) pulsates from three holes simultaneously. Bolshoi creates a unique water cascade from a huge gryphon-like cavity.’

Another Sakharny – sugar – shoots upwards ‘with a crown sparkling in the sunshine’, and Fontan (Fountain) creates a narrow ‘milky’ jet.

‘Leshiy (Sylvan) groans in semi-underwater condition, Khrustalny (Crystal) glitters, while Grot (Grotto) keeps silent for years in order to once (send) tens of thousands of turbid water from the slope to the river.

‘The spectacle of fountain geysers is supplemented by more than 200 pulsating hot and steaming springs, steam and gas jets, bowls with red boiling clay, steaming cavities whooing like owls, hot and warm lakes and brooks with waterfalls.’

As he said, the valley ‘is a unique ecosystem and a special microclimate for plants and animals. Spring comes to thermal sites a month earlier than usual, at the end of April.’

The reserve takes its name from the perfectly-coned and snow-crowned Kronotsky Volcano.

One of the world’s most scenic volcanoes, its highest point rises 3,527 metres (11,552 feet) above the level of the Pacific Ocean. Kept silent for now by a volcanic plug, its last eruption was in 1923.

Uzon Caldera – the remnants of a volcano that ‘blasted itself open’ some 40,000 years ago. Picture: Viktor Gumenyuk, Kronotsky Nature Reserve

At its base is a lava-dammed lake entrapping some 30 million landlocked salmon, otherwise known as lunch for the local bears, reputed to be the best-wed anywhere.

Another volcano, the Krasheninnikov, named after tsarist explorer and naturalist Stepan Petrovich Krasheninnikov, comprises two overlapping stratovolcanoes inside a large caldera. This has been dormant since the 16th century.

More famous is the Uzon Caldera, the remnants of a volcano that ‘blasted itself open’ some 40,000 years ago.

This is now a cavernous bowl, ringed by a ridge, some 12 kilometres across and named after the spirit Uzon, a mighty presence in the tales of the native Koryak people. Across its terrain are ‘fumaroles and hot springs and sulfurous lakes, blueberry-and-heather tundra, forest patches of birch and Siberian dwarf pine’.

‘The story told by Koryaks about Uzon and his caldera has the ring of a parable,’ explained Quammen, in an enchanting description.

‘He was a friend to humanity, quieting earth tremors, stifling volcanic eruptions with his hands, doing other good deeds; but he endured a lonely existence, living secretively atop his own mountain so that evil spirits wouldn’t come and destroy the place. Then he fell in love.

It is ‘a protected area which is kept forever wild’, a ‘nature sanctuary’ and there are more than 100 in Russia of which this is the doyen. Pictures: Alexey Bezrukov, Liana Varavskaya, Lyudmila Figura, Igor Shpilenok

One of the world’s greatest natural wonderlands in Rusisa’s Land of Fire and Ice ‘She was a human – a beautiful girl named Nayun, with eyes like stars, lips like cranberries, eyebrows as dark and glossy as two sables.

‘She loved Uzon in return, and he took her away to his mountain. So far, so good. But after some years of marital bliss and isolation, Nayun began to pine for her human relatives. Couldn’t she have a visit with them somehow?

‘Uzon, wanting to please her, made a desperate and tragic mistake: He spread the mountains with his mighty arms and created a road. People came, curious and disruptive.

‘Now everybody knew Uzon’s secret hideaway, including those evil spirits. The earth yawned with a horrible crash having absorbed a huge mountain,’ in one telling of this tale, by G. A. Karpov, ‘and mighty Uzon turned into stone forever.’

‘You can see him there even today, petrified into a high peak on the northwestern perimeter of the caldera, his head bowed, his arms stretched around to form the rim.’

Among other phenomenon here is one nicknamed Death Valley, not discovered unto 1975.

Kronotsky Biosphere Zapovednik, should be free of tourists and hunters, and instead be visited solely by scientists engaged in serious science. Pictures: Kronotsky Nature Reserve

Another Western writer to venture here, Fred Strebeigh, explained it: ‘On windless days, its gases – laced with hydrogen sulphide and cyanide – settle near ground level and kill.

‘Its victims have included foxes, bears and even yellow-beaked Steller’s sea eagles on the rare occasion they stray from the fine fishing along the zapovednik’s Pacific shoreline, less than 20 km southeast.’

Another treasure here is ‘Stained Glass’, first documented by scientist Ustinova whose ashes were scattered in the Valley of the Geysers after her death aged 96 in 2009, a multicolored valley wall tinted with reds, yellows, greens and blues by a mix of residue from a score of large and small vents.

As Strebeigh recounted: ‘Beneath Stained Glass, we sat before the globe’s greatest natural calliope – a steam-powered organ driven by the earth’s heat – each blowhole piping its own pitch in our now-private sanctuary.

‘As rangers kept telling me, geyser beauty gets greater after the last helicopter leaves and evening light turns slant.’

One travel company, appropriately called Lost World, which offers 16 day trekking trips to Kamchatka, including stays in Kronotsky in cabins or tents, describes it accurately as ‘one of unique places created by Nature on our planet’.

At its base is a lava-dammed lake entrapping some 30 million landlocked salmon, otherwise known as lunch for the local bears. Pictures: A.Bichenko, Kronotsky Nature Reserve

Places on the tours are strictly limited, and don’t come cheap, considering the air fares needed from Europe or North America, to reach this place. The 2016 tour alone was priced at 3380 euro, but yet again, perhaps this is amazing value in unlocking the sights here.

Among the gems the handful of tourists are promised is to see ‘a picturesque plain where bears feed on wild berries. This valley is interesting for the crater-shaped-pits 25 – 150 metres in diameter and 25 – 40 metres deep, filled with hot and unusually coloured thermal water’.

Day 4 promised: ’12 km trek and excursion to the Valley of the Geysers. See over-twenty geysers and numerous mud pots. Water-and-steam fountains bemuse with their beauty and strength. Overnight in tent camp on Sestrenka River bank.’

Tourists were told to expect to see a ‘beautiful volcanic landscape from the height of the helicopter flight’, and at some point there was bathing in thermal hot springs.

The website for Lost World is http://www.travelkamchatka.com for future travel possibilities to Kronotsky and elsewhere on the Kamchatka peninsula.